Major volcanic eruptions were not responsible for dinosaur extinction, new research suggests

New research has provided fresh insights into the dramatic events surrounding the extinction of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago.

The extinction of the Dinosaur was a tumultuous time that included some of the largest volcanic eruptions in Earth’s history, as well as the impact of a 10-15 km wide asteroid. The role these events played in the extinction of the dinosaurs has been fiercely debated over the past several decades.

New findings, published today in the journal Science Advances, suggest that while massive volcanic eruptions in India contributed to Earth’s climate changes, they may not have played the major role in the extinction of dinosaurs, and the asteroid impact was the primary driver of the end-Cretaceous mass extinction.

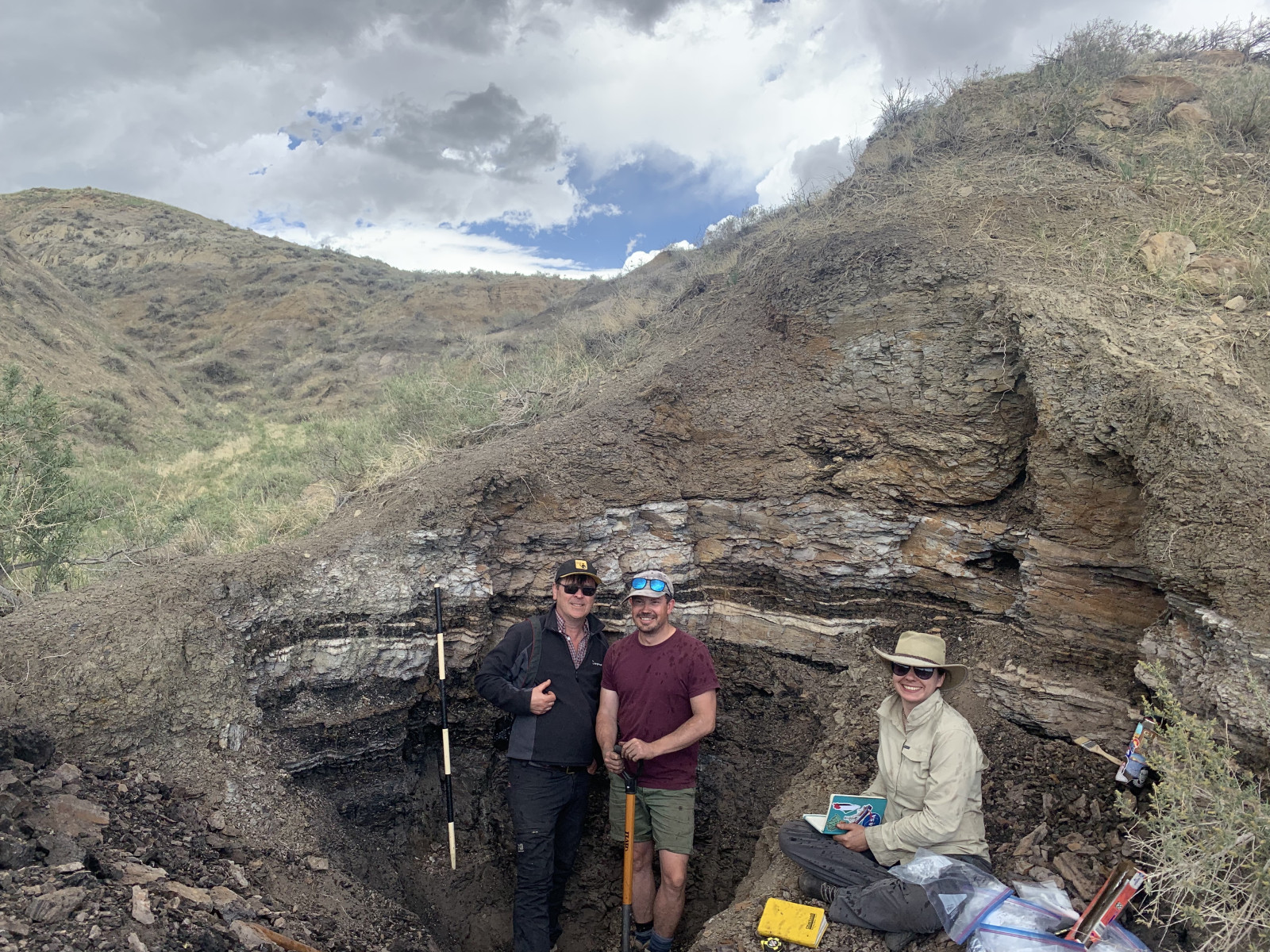

By analysing ancient peats from Colorado and North Dakota in the USA, the researchers – led by The University of Manchester – reconstructed the average annual air temperatures in the 100,000 years leading up to the extinction.

The scientists, including from the University of Plymouth, Utrecht University in the Netherlands, and Denver Museum of Nature and Science in the USA, found that volcanic CO₂ emissions caused a slow warming of about 3°C across this period. There was also a short cold “snap” — cooling of about 5°C — that coincided with a major volcanic eruption 30,000 years before the extinction event that was likely due to volcanic sulphur emissions blocking-out sunlight.

However, temperatures returned to stable pre-cooling temperatures around 20,000 years before the mass extinction of dinosaurs, suggesting the climate disruptions from the volcanic eruptions weren’t catastrophic enough to kill them off dinosaurs.

Dr Lauren O’Connor, lead scientist and now Research Fellow at Utrecht University, said: “These volcanic eruptions and associated CO2 emissions drove warming across the globe and the sulphur would have had drastic consequences for life on earth. But these events happened millennia before the extinction of the dinosaurs, and probably played only a small part in the extinction of dinosaurs.”

The fossil peats that the researchers analysed contain specialised cell-membrane molecules produced by bacteria. The structure of these molecules changes depending on the temperature of their environment. By analysing the composition of these molecules preserved in ancient sediments, scientists can estimate past temperatures and were able to create a detailed “temperature timeline” for the years leading up to the dinosaur extinction.

Dr Tyler Lyson, scientist at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, said: “The field areas are ~750 km apart and both show nearly the same temperature trends, implying a global rather than local temperature signal. The trends match other temperature records from the same time period, further suggesting that the temperature patterns observed reflect broader global climate shifts.”

Bart van Dongen, Professor of Organic Geochemistry at The University of Manchester, added: “This research helps us to understand how our planet responds to major disruptions. The study provides vital insights not only into the past but could also help us find ways for how we might prepare for future climate changes or natural disasters.”

The team is now applying the same approach to reconstruct past climate at other critical periods in Earth’s history.